Hell Through Milton's Eyes

Satan's First Steps into the Abyss

Originally Published at Medium.

Do you ever wonder what hell looks like? Or what would happen if you ever ended up there?

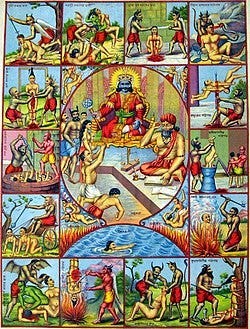

In Hinduism, the religion that I follow, the concept of hell, known as Naraka, is not a place of eternal damnation, but rather a temporary realm of suffering for those who have accumulated negative karma. It is part of the cycle of rebirth (samsara) and is not the final destination for the soul. Hinduism emphasizes liberation (moksha) from this cycle through good karma and spiritual practice, rather than eternal punishment or reward.

Growing up, I heard descriptions of hell many times, but I never really stopped to imagine it. I mean, why would I bother to? Like most things in my life, I accepted what I was told and moved on. Classic autopilot mode: engaged. The fine art of nodding and moving on.

It was difficult for me to grasp the concept of death, especially after learning about the concept of life and rebirth.

Death was seen as a form of liberation, and I wasn’t worried about it in the slightest.

( Except for that one time where I got shit scared because I thought I would die due to drinking a fizzy drink right after consuming a packet of Kurkure, a brand of spiced crunchy puffcorn snacks made up of rice, lentil, and corn. Don’t judge me, my sister tricked me into thinking that I would vomit blood, and I have emetophobia. Peak childhood trauma courtesy of junk food marketing.)

I didn’t think much of it until one day, a very different vision of hell landed in my hands. I came across a Christian description in a newsletter: “a lake that burns with fire and sulfur” (Rev. 21:8).

Outside my own cultural lens, other descriptions of hell started to surface, which piqued my interest, but I never made any efforts to dive deeper into it.

But when I read Paradise Lost, I couldn’t help but imagine hell in vivid detail.

The newsletter was just imagery on the page. But Milton? He made me see hell. And once you see it Milton’s way, you can’t really unsee it.

Milton’s imagery is striking throughout the epic, yet a few lines stood out to me — lines 231 to 242. Today, I’ll step into “research nerd” mode and unpack these lines.

Setting the Stage

Before line 231, Milton has already described hell as barren, dark, and infernal. In the lines that follow, Satan’s defiance grows, and he aims to rebuild a new order in Hell.

Before we begin to imagine Milton’s hell, here’s how the world viewed it for the first time :

Hell imagined through Milton's eyes

Here are the lines (231–236):

“Of subterranean wind transports a hill / Torn from Pelorus, or the shattered side / Of thundering Etna, whose combustible / And fuelled entrails thence conceiving fire, /Sublimed with mineral fury, aid the winds, / And leave a singèd bottom all involved /With stench and smoke…”

Volcanoes and Cataclysm

Milton invokes powerful imagery of volcanoes — Pelorus and Mount Etna — both of which are real geographical places in Sicily, which is located in Italy.

Pelorus: A raised mass of land that extends out into the sea in northeastern Italy.

Pelorus is used as a metaphor comparing Satan’s violent motion to a mountain being torn from the Earth and hurled, a metaphor for his terrible strength, destructive energy, and the epic scale of his fall.

This conveys the immense physical force of Satan, the chaotic, earthquake-like violence of his presence, and the terrifying scale of events in Hell. This simile of Pelorus highlights how superhuman or divine Satan’s power appears, even though he’s fallen.

Milton likely chose Pelorus because it’s a known classical landmark. It’s linked to seismic and volcanic imagery, emphasizing Hellish force. Its removal from the Earth (in the metaphor) evokes cataclysm, a large-scale and violent event in the natural world, reflecting the violent, unnatural rebellion of Satan.

Mount Etna: It is one of the largest and most famous active volcanoes of Europe. It symbolizes fiery destruction, “mineral fury,” and volcanic power in Milton’s metaphor for Hell’s landscape. Volcanoes do create a vivid imagery of hell.

Sicily is known for its volcanoes and earthquakes, so it was a powerful and terrifying image for Milton to draw on when describing Hell.

This region had long been associated with the classical underworld, particularly Hephaestus, also known as Vulcan (the Roman god of fire), believed by the ancients to be residing under Mount Etna. Fire and its destructive nature definitely do resemble the image of hell.

Giants Beneath the Mountain

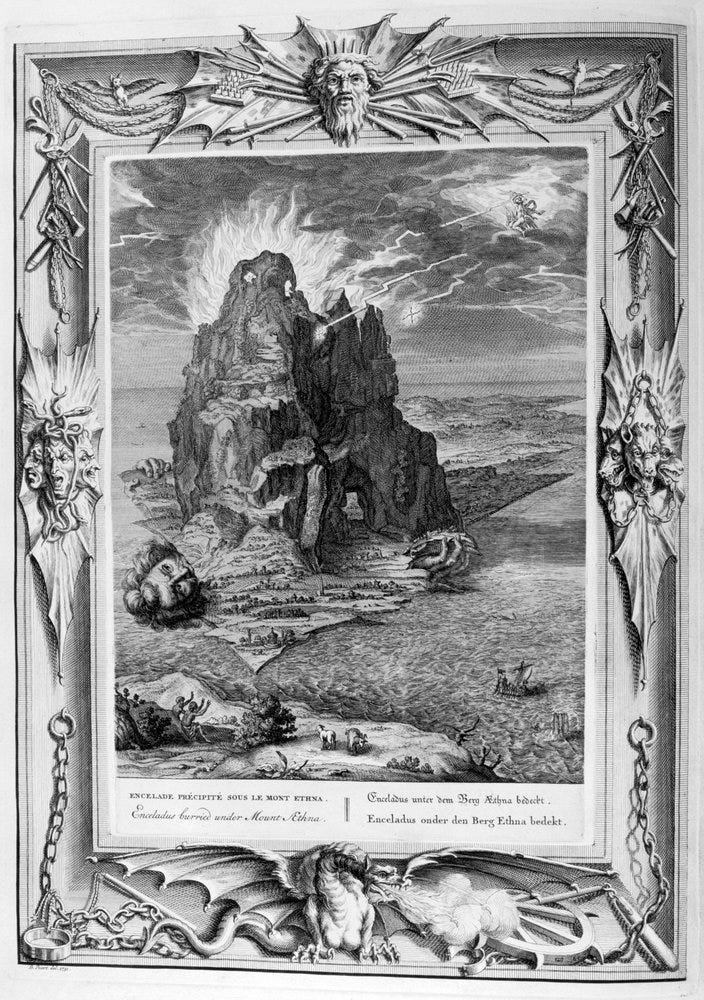

This volcanic imagery is terrifying enough, but it becomes even more powerful when Milton ties it to a giant buried under the earth by mentioning Enceladus.

In Greek mythology, Enceladus was one of the Giants, the offspring of Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (Sky). Enceladus was the traditional opponent of Athena during the Gigantomachy, the war between the Giants and the Gods, and was said to be buried under Mount Etna in Sicily. The volcanic eruptions of Mount Etna were believed to be Enceladus groaning or struggling beneath the mountain.

Milton refers to Enceladus as a metaphor to describe Satan’s vast, defeated, but still powerful form lying in Hell after the fall. Satan rising from the lake of fire is compared to Enceladus stirring beneath Mount Etna. The size & power of Enceladus are similar to the stature of Satan. Satan, like Enceladus, is enormous, awe-inspiring, and still threatening, even when defeated.

Just as Enceladus was defeated by Zeus (also a God), similarly, Satan was also cast down by God; both figures are rebels against supreme authority and were defeated by a higher power. This line also creates a mythological allusion as it enriches the epic tone, aligning Milton’s work with classical epics like Homer’s and Virgil’s.

Hell is imagined as volcanic and fiery, like Mount Etna; destructive, unstable, and seething with suppressed rage. Thus, these places by Milton are used to describe the catastrophic disruption, and we see how Hell’s winds and fires violently reshape the landscape.

Volcanic Hellscape

The tearing up of mountains by “subterranean wind” gives Hell a sense of geological power and horror. The comparison to earthly volcanoes can be interpreted as Milton grounding the supernatural in natural imagery.

The idea of “mineral fury” suggests explosive rage, perhaps a reflection of Satan’s own rage and ambition. Here, the choice of words by Milton, such as ‘entrails’, ‘conceiving’, and ’bottom’, also gives the hellish landscape an anthropomorphic touch.

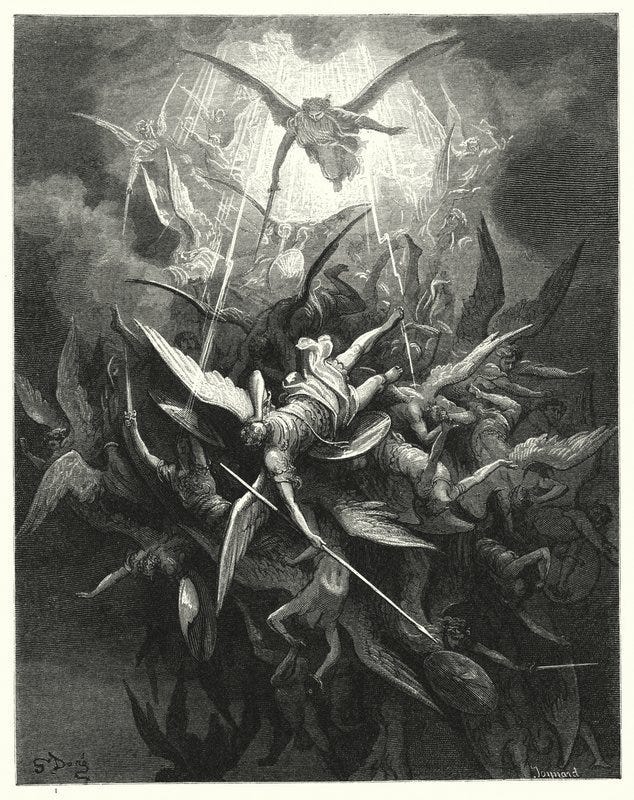

“Singed” here means slightly burned or scorched (especially the outer layer). Milton uses vivid imagery to describe how Satan, hurled from Heaven by God’s thunderbolt, crashes through space and ends up in the burning lake of Hell.

Doré’s engraving helps us picture this moment of the fall:

The term “singed bottom” evokes an image of something scorched by divine fire or punishment, possibly referring to Hell’s burning surface, or Satan’s own scorched body after his fall.

It emphasizes the fiery, destructive nature of Hell, contrasting sharply with Heaven’s light. It reflects Satan’s fall from grace and divine punishment. It also reflects themes of judgment, loss of divine favor, and transformation from an angel of light to a scorched, ruined figure.

Here is Line 237:

“Such resting found the sole of unblest feet.”

The Irony of Rest

This line is deeply ironic. The “unblest feet” are those of Satan, once the most glorious of angels, now a fallen being who finds “rest” not in peace, but in a scorched, sulfurous wasteland which is hell.

Milton seems sarcastic here, where he implies that Satan may never find true rest. So, “unblest feet” refers to Satan’s own feet, or metaphorically, his entire being, now fallen from grace, no longer holy or touched by God’s blessing.

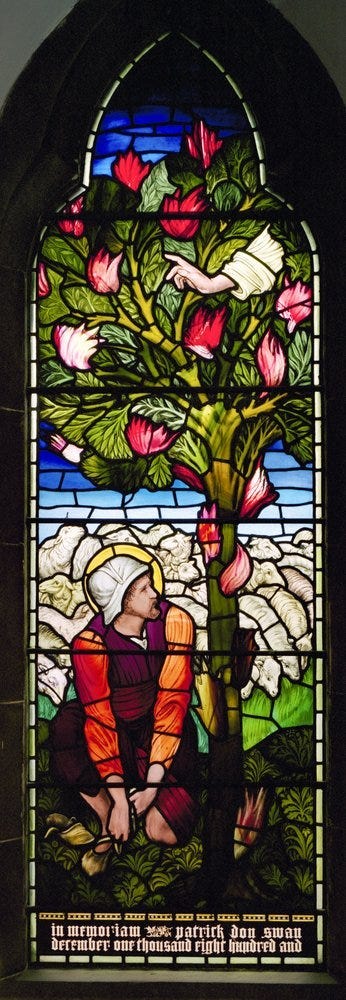

It’s an ironic reversal of biblical or sacred moments, like when Moses is told to remove his shoes because he stands on holy ground, which is depicted in the saying “like Moses at the burning bush.”

In the biblical story of Moses and the Burning Bush, God appears to Moses in a burning bush on Mount Horeb, commissioning him to lead the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt. His abiding presence is displayed. The bush is on fire but not consumed by the flames, symbolizing God’s presence and power.

The burning bush was a manifestation of God’s glory or uncreated energies. God reveals his name as “I AM WHO I AM,” signifying his eternal and unchanging nature, and he tells Moses to go to Pharaoh with a message that God will not let the Israelites stay in Egypt.

However, this, in contrast, is the unholy ground.

This line captures the tragic fall of a once-glorious angel. Even where he stands is marked by divine rejection. It contrasts with his earlier grandeur and foreshadows his false throne, which is elevated, but in a cursed land.

Here are the lines 237 to 240:

“Him followed his next mate, / Both glorying to have ‘scaped the Stygian flood / As gods, and by their own recover’d strength, / Not by the sufferance of supernal power.”

Defiance with Beëlzebub

In these lines, we see Satan standing on the burning plains of Hell, having just escaped the Stygian flood. The Styx or Stygian (which also means “hate” and “detestation“)is the infernal river of hell in Greek mythology that formed the boundary between Earth and the Underworld.

Alongside him is his closest companion, Beëlzebub, and together they falsely pride themselves (which is evident with the use of the word glory) on having escaped through their own power, and not God’s mercy.

I found this funny because I thought this was a classic Satan move(even though I don’t know much about him): get thrown into a lake of fire, barely crawl out, and then brag about how it was totally your own power. Textbook delusion energy.

This is a moment of defiance; Satan clings to his identity as a god, even in damnation.

This sets up one of the central debates of Paradise Lost: how much of an antagonist Satan really is, and whether Milton unintentionally made him a kind of tragic hero.

Closing Teaser

Hell, in Milton’s vision, is not just a pit of fire; it is volcanic, mythological, and tragically ironic. Satan’s defiance burns as fiercely as Etna, yet his “resting place” is only scorched ground.

So that’s Part 1: Satan as volcanic, mythological, and defiantly scorched figure. Part 2 gets even hotter because that’s where theology steps in.

In Part 2, I’ll explore the theological debate that arises here: is Satan simply the villain, or is he something far more complicated?

Thank you for reading. Part 2 will be out soon (with the bibliography for both parts included there).

NOTES

¹Hieronymus Bosch was a late 15th-century, early 16th-century Dutch painter. A highly imaginative and influential artist, he is best known for his vivid and often frightening depictions of Hell. While this was not an uncommon subject in medieval European painting, Bosch still stood out above his contemporaries.

²Description Of The Image: A large central panel portrays Yama, the god of death (often referred to as Dharma), seated on a throne; to the left stands a demon. To the right of Yama sits Chitragupta, assigned with keeping detailed records of every human being and, upon their death, deciding how they are to be reincarnated, depending on their previous actions. A woman and two men await their judgment. The rest of the print is compartmentalized into fourteen smaller panels, and each image portrays a different way demons torture sinners. These vary from being pierced by a spear to having your entrails removed. Bengali inscriptions detail each occurrence.

The number and names of hells, as well as the type of sinners sent to a particular hell, vary from text to text; however, many scriptures describe 28 hells. After death, messengers of Yama, called Yamadutas, bring all beings to the court of Yama, where he weighs the virtues and the vices of the being and passes a judgment, sending the virtuous to Svarga (Svarga is often translated as heaven, though it is regarded to be dissimilar to the concept of the Abrahamic Heaven) and the sinners to one of the hells. The stay in Svarga or Naraka is generally described as temporary. After the quantum of punishment is over, the souls are reborn as lower or higher beings as per their merits. (Taken from Wikipedia)

³Fra Angelico, born Guido di Pietro and known as Giovanni da Fiesole, was a Renaissance painter and Dominican friar celebrated for his religious art. Ordained around 1425, he became renowned for his vivid depictions of holy figures, which combined the emerging principles of perspective with deep spiritual significance.

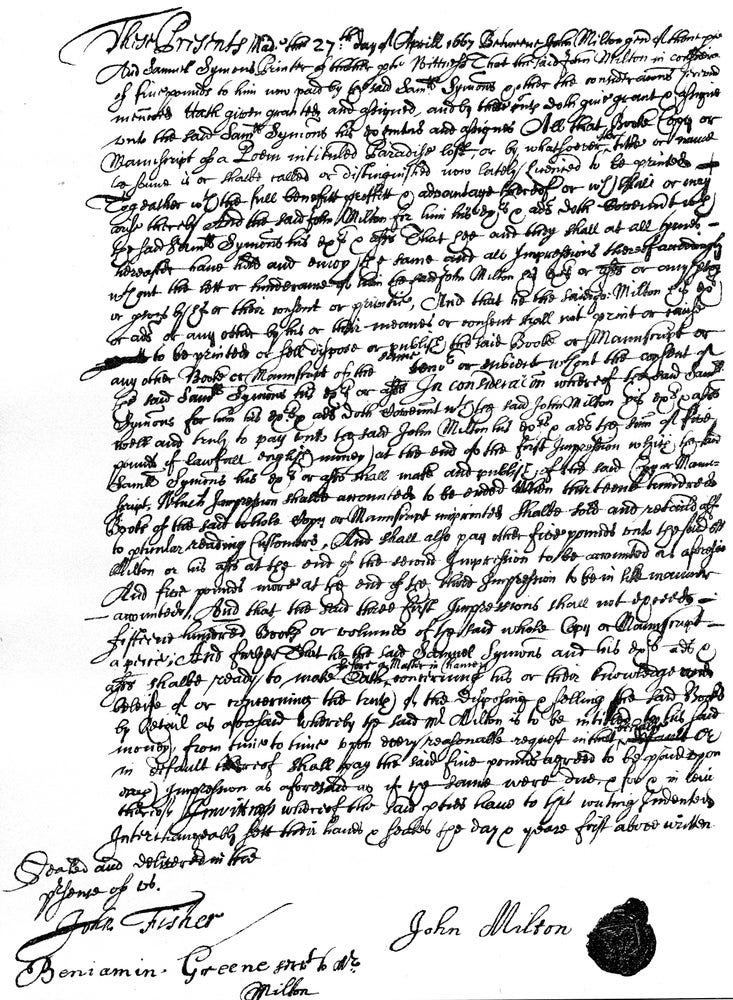

⁴Milton, who was blind and financially strained at the time, received only £5 upfront, with the promise of another £5 for every 1,300 copies sold, up to a total of £20. The deal shows how little value Paradise Lost was expected to have commercially at first, despite its later fame as one of the greatest works of English literature. The document survives in the British Library and is one of the earliest examples of a formal copyright agreement for a literary work.

⁵Etching and engraving by the French artist Bernard Picart or Picard, a French draughtsman, engraver, and book illustrator in Amsterdam, with an interest in cultural and religious habits, part of his series Le Temple des Muses (The Temple of the Muses). The artwork depicts the Greek mythological giant Enceladus being crushed beneath the volcano, with the flames of Etna representing his fiery breath, and quakes from the island of Sicily caused by his movements.

⁶ In Gustave Doré’s wood engraving for John Milton’s Paradise Lost, the dramatic moment is captured when Satan and his rebellious angels are expelled from Heaven as described in Book I, lines 44–45 of the epic poem. The image depicts a scene of turmoil and chaos as the fallen angels are cast out, emphasizing the powerful emotions and intense clash between good and evil. Doré’s detailed artwork brings to life the epic tale of Milton’s iconic work. It was part of Doré’s complete illustrated edition of Paradise Lost, which cemented the way many readers visualize Milton’s cosmos. His engravings blend Romantic sublimity with biblical awe, making them enduring companions to the text.

⁷Burne-Jones stained glass window on the west side of St Brycedale Church of Scotland, St Brycedale Avenue, Kirkcaldy, Fife. St Brycedale Church was built for the Free Church in 1877–9 by James Matthews of Aberdeen. Its spacious interior contains stained glass designed by prominent artists, including Burne-Jones. This stained-glass window shows Moses and the Burning Bush (left) and the Burial of Moses (right). It was designed by Edward Burne-Jones and made by Morris and Company in 1892. Sir Edward Colley Burne-Jones (1833–98) was a member of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, which reacted against Victorian taste by adopting a style influenced by art from before the age of the Italian painter Raphael. Description taken from:

Burne-Jones Catalogue Raisonné | Moses and the Burning Bush; The Burial of Moses stained glass St…

The official catalogue raisonne of Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones Bt. including works, expertise, thesis and articleswww.eb-j.org

⁸Created in 1802, the oil-on-canvas work shows Satan rousing his second-in-command, Beelzebub, after they have been cast into Hell. The painting is housed at the Kunsthaus Zürich in Switzerland.

⁹Paul Gustave Louis Christophe Doré was a French printmaker, illustrator, painter, comics artist, caricaturist, and sculptor.

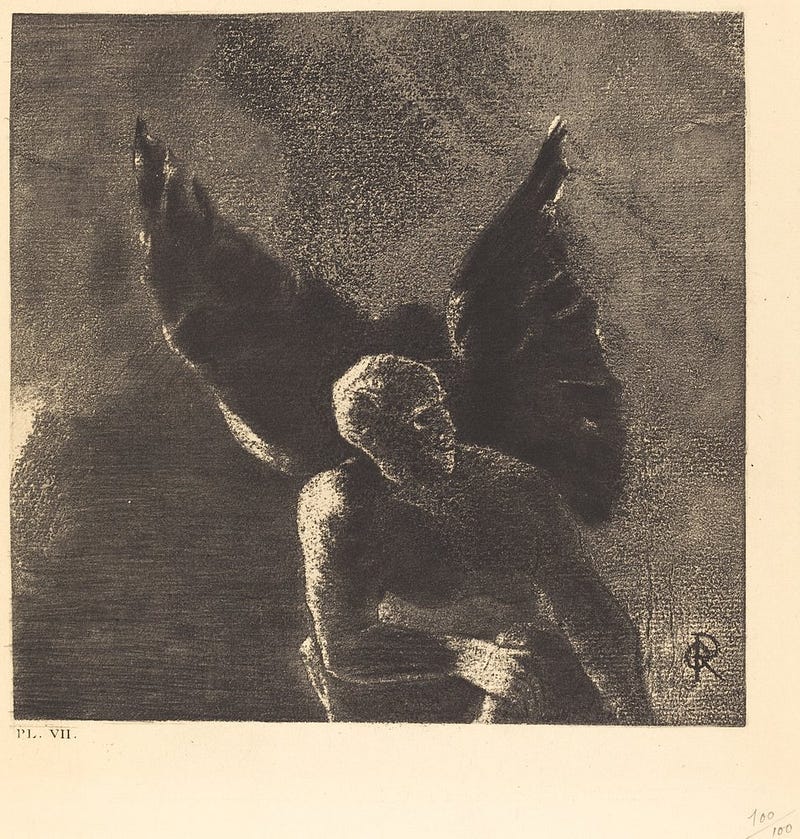

¹⁰“Glory and Praise to You, Satan…” is a lithograph by the Symbolist artist Odilon Redon, created in 1890 as part of his illustrations for Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil). This powerful print depicts a fallen angel, embodying the conflict and silent despair of Satan.